Jose Luis Alvarez Rodriguez, Cuban poet and educator.

«The average age of a man in the Bronze Age was eighteen; in the Roman era, twenty-two. Paradise must have been beautiful then. Today, it must be terrible. When a man reaches forty, he has no chance of dying beautifully. No matter how hard he tries, he will die of decay. He must force himself to live.»

Mishima

On the morning of November 26, 1970, Mishima’s wife, while driving through the streets of Tokyo, heard the news of the «incident» on the car radio. After dropping off their children at school, she fainted at a traffic light. At home, the writer’s father was terrified by the live images being broadcast on television channels: Yukio Mishima and four young followers had seized the Chief of Staff of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces in his office, tied him to his chair, and shouted three martial and noisy cheers for the Emperor. They then forced the military officer to witness Mishima’s suicide by seppuku. Once Mishima successfully made the cut, one of the young men beside him decapitated him at the right moment. Another one, Morita, tried to repeat the scene, but tears and nervous tension prevented him from making a proper abdominal cut, so he begged another young man, Furu Kaga, to deliver the final blow. The two heads were neatly placed vertically on the floor, the General’s eyes seemed ready to pop out of their sockets—the «incident» had concluded, and it was necessary for the whole world to know that there were still young people willing to die for the ideals of imperial Japan.

The word seppuku may sound strange to us, semantically it refers to suicide by honor among the samurai class, and for Cubans, the word hara-kiri is more familiar, although it has lost its original semantic meaning in our country. For many years, it has become synonymous with a sincere act. For example, «the director of such company, Mr. So-and-so, did the harakiri during the assembly in front of all his colleagues before they fired him,» meaning that Mr. So-and-so spoke about all the bad and good things he had done during his tenure, of course, focusing more on the bad things because hara-kiri is a serious matter.

Revisiting the past is an adventure that always enriches us and sometimes brings terrifying ghosts into our path through life—not like Wilde’s Canterville Ghost, which was charming, playful, and witty, or like fairies and gnomes who signal us with complicit happiness.

For the child that I was (and I believe I still am to avoid committing seppuku) who insisted on reading things that were not suitable for his age and watched «restricted for children under twelve» movies through the sacred holes in the old wooden doors of the Avellaneda cinema-theater in the city of Camagüey, besides other sinful little things he did while neither reading nor watching movies, it is now, in the inexorable flow of time (and consciousness), a part of my lovely past to remember that crouching on the hard cement doorstep, that child used one eye first and then the other to peek through one of the holes that opened up the magical screen of the mysterious venue. I confess that child took pleasure in it and later, during bath time at home, delighted himself with the image of Claudia Cardinale, the girl with the suitcase, descending a staircase with an unforgettable smile. A white towel, of course, because most of the movies shown were in black and white, semi-covered his imagined, full, and atrocious nakedness, and those childish eyes (one first, the other after, because the hole was not «suitable for children under twelve» but rather for a single eye) experienced another afternoon of cinematic revelry when a proud and impoverished Japanese man insisted on having a bamboo dagger (not a katana, not a hamidashi) penetrate his abdomen. He would lean his body and rest it on the whitest of platforms, so that it would finally penetrate, and the sweat and the grimace on his face would reveal first a small wound, then a larger one, and splat, the intestines would have to emerge, like the pig’s on Christmas Eve laid out on the table in my backyard. The young man begged the samurai standing beside him, with the raised sharp blade, to please decapitate him, but the act had to be completed… Then came the complicity with other cinephile friends or hole-in-the-wall cinephiles who, in our homes, with a kitchen knife, pristine sheets imitating costumes, and red dye for hair tint serving as blood, performed our Camagüeyan seppukus or hara-kiris before the astonished eyes of our mothers, grandmothers, aunts, and sisters, amazed by such a strange game and anxious about having to spend money from the monthly budget to buy new sheets (back then, you could do that with little money).

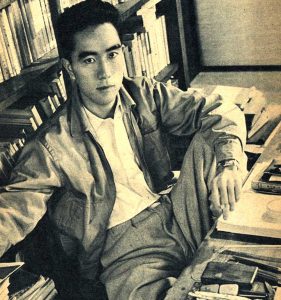

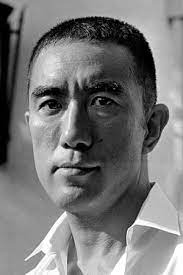

During these same years, in Tokyo, Paris, New York…, the writer Yukio Mishima (Kimitake Hiraoka), the prodigious child of Japanese literature, one of what we could call the cursed writers of the 20th century, among whom there are many to choose from, triumphed with his works and eccentricities. He was already carefully preparing his final spectacle: committing seppuku and leaving an impressive legacy of works for a writer of his age. These works included essays, short stories, novels, plays, photographic albums, and more, which made him one of the most insightful critics of post-war Japanese society and shaped the course of contemporary literature in his country.

I confess that I know more about the life of the author in question than about his actual work, not out of negligence, but for the simple reason that it is difficult to find his books. At this stage of my life, it would be an act of injustice to subject the same eyes that were glued to the dusty doors of Avellaneda to read this immeasurable work on a computer screen, including his photos and films. Mishima should never be thought of as a calm writer, although he was dedicated and consistent. He was a character pursued by the media, not only for the undeniable value of his work, but also for his ability to reveal the two faces he always had: the boy who read Anunzzio, Radiguet, Malraux, Thomas Mann, who had a profound knowledge of the best of Japanese literature, who read and wrote English perfectly, frequented gay nightlife venues with his friends, brothels, and the slums, noting everything, observing every detail, and then locking himself away for several days to write extensively. He was a young man capable of skydiving, conducting a symphony orchestra, piloting an F-102 aircraft, writing a ballet and performing in it, practicing fencing, boxing, karate, horseback riding, weightlifting, and publicly challenging left-wing students at a university with respect.

His writings should not be approached with a Western perspective because there is a risk of not understanding him. To understand Mishima, one must have at least a general knowledge of the ethical and aesthetic principles of the Japanese people because his work contains Zen philosophy and a staunch defense of the Japanese being. It is about the fierce mask that a warrior must wear with a beautiful and noble face, the suggestion of deliberately presenting an incomplete work for the reader to decipher, the transmutation of souls that served as a technical element to shape his tetralogy «The Sea of Fertility»: «Spring Snow,» «Runaway Horses,» «The Temple of Dawn,» and «The Decay of the Angel.» These works take us on a journey through the history and vicissitudes of Japan from 1912 to 1970, delving into the 19th century starting with the «Divine Time Association» in Kumamoto (1876) during the samurai uprising. Mishima vividly recreates this event, a warlike drama with a great romantic aura, in which 200 of these warriors, already cast aside by Emperor Meiji’s order to Westernize Japan, attack a fortress occupied by 2,200 men armed with rifles and artillery. The result is imaginable, although they incapacitated many soldiers with their flashing katanas. Forty-six of those who managed to survive committed seppuku, facing east towards the Emperor’s residence, against whom they had rebelled. This event is portrayed with great poetry and, at the same time, heartbreaking realism in his novel «Runaway Horses.» Obsessed with seppuku and this specific event, Mishima embraced the practical futility as a merit.

There are more Japanese elements: the unity between the real and the imaginary world is more important. Let’s say it’s not the contemplation of the moon itself, but its image that matters. For example, a large cypress vase is placed in such a way that the water it contains reflects the moonlight, allowing it to be contemplated. That’s why it has been said that the Japanese value the copy of reality more than reality itself. Then there is refinement, attention to detail. In one of his works, two characters discuss the convenience of having a pet. One of them says, «Poets don’t mention those animals, and what doesn’t fit in a poem has no place in my house; it’s a rule in my family.» There’s also the culture of the brothel, the preeminence of visual values, bells that call the wind, and of course, tragic elements. The Japanese are known for being at their best in extreme situations, accepting death with dignity. Reading «The Temple of the Golden Pavilion» has demanded revisits because, like all classic works, it requires them. I also mention two of his short stories: «The Pearl» and «Patriotism.» They are distant in theme and style but converge in representing the two sides of Mishima, just as they represent the two sides of Japan: the chrysanthemum and the sword.

In my opinion, «The Pearl» is one of the great short stories of world literature, comparable to Guy de Maupassant’s famous story «The Necklace.» Although there are no deaths, it penetrates accurately into the female psychology, and it is more chrysanthemum than sword because the latter emerges beneath the veil of cruel vanity in certain contemporary Japanese high society ladies.

As for «Patriotism» or «Rite of Love and Death,» neither comedy nor tragedy, according to Mishima himself, it can be said to be a story of supreme happiness. In Japan, in 1936, a newly married lieutenant learns that his best friends are among those who have revolted against the Emperor. After making love to his wife, he writes a letter of apology to his parents and then commits seppuku in front of his wife, who delicately and precisely stabs herself in the neck until she dies. If William Shakespeare had known about this real story, it would have resulted in another tragedy somewhat related to «Romeo and Juliet.» There lies the delicacy, the detail, the erotic act linked to death, making it more erotic, or especially erotic.

As readers of Mishima, we must set aside the common assumption that has been established about him: his fascist ideology. The Japanese have tried to deceive us since their defeat and the American occupation when they decided to hide the sword and only show the chrysanthemum, in order to convince the invaders that they are peaceful or harmless, hardworking, meticulous in their floral arrangements, delicate in their gardens, skilled in the art of miniature trees, and hosts of precious cherry and chrysanthemum festivals. Japan, therefore, has been stripping itself of the philosophy of death and, upon entering a consuming society, industrialization, and significant technological advancements, they have lost their own identity.

Mishima had a reckless grandfather and a grandmother who isolated him from the external world during his childhood. Some biographers say that she made him play with dolls with his female cousins and dressed him as a girl. However, that grandmother knew how to introduce him to the traditions of his distant samurai lineage. She enrolled him in a noble school where he became the top student in his graduating class, earning him the Silver Watch in 1944 as a gift from the Emperor himself.

This friendly, talkative, narcissistic, exhibitionist, some say even sexually morbid, some say homosexual and other seasonings, make it even more attractive to me because, as Marguerite Yourcenar says in her biographical and literary study Mishima or the Vision of the Void: «The time has already ended when one could savor Hamlet without worrying much about Shakespeare: the crude curiosity for biographical anecdotes is a characteristic of our time, multiplied by the methods of a press and media that are directed at an audience that reads less and less.»

Reading Yukio Mishima is to confront violence and delicacy, the child that I was, who saw a seppuku in a Japanese film from the 60s, and who with his little index finger poked and poked to widen the hole of the patient door, was aroused by the macabre spectacle of death, and today, with that same finger, has eagerly turned the pages of the few books by Mishima that he has obtained, or the printed pages with his stories, and has once again convinced himself that what matters in a writer is his work. Mishima deserved the Nobel Prize that he never obtained, although he did achieve the most important awards in his country, and with his spectacular suicide, he showed the sword and the chrysanthemum, a beautiful and not useless death, because anyone who defends the identity of a culture deserves all respect. If the Emperor said that he was no longer the god for whom the kamikazes sacrificed their lives, Mishima knew, because he wasn’t foolish, that the Emperor was not a god, but it was essential for everyone to believe it. He wanted to restore old lost values in a society that was moving away from old values. At least I don’t believe in useless deaths, his seppuku is one more book, still alive, in the always attractive and mysterious Japan.

Your gift may be in my store

Connect with Akerunoticias, a newspaper that arrives with a selection of the most interesting content of the moment. It doesn’t matter if you live anywhere else on the planet, receive links to the most relevant news of the moment in your email inbox. Subscribe to our YouTube channel and enable notifications, and follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

We also invite you to visit the CLUB DEL CREATIVO ONLINE

Their articles will guide you in the real and effective way to make your online business WORK. Join the CLUB. Subscribe and receive FREE documents, ebooks, support, tutorials, and access to conferences. If you subscribed and haven’t received the bonus gift, remind us through the CONTACT FORM.